Dissident Dialogues: CJ Hopkins

My Dinner with CJ: On the New Normal Reich; “Reality”; Cowardice, Complicity, & Courage; His Controversial Take on Mass Formation; & Killing Beckett

CJ Hopkins

If you read me, you probably read CJ Hopkins, but if you are one of the rare individuals who has not yet savored CJ’s succulent satirical offerings, then head over to his Substack and sign up because his is a singular, requisite voice:

Not only is CJ my favorite satirist—living or otherwise—but he is an individual of intrepid integrity and the writer I consider closest to me in both spirit and mission. His ferocious wit and cantankerous courage make him a formidable ally in the present existential showdown with tyranny.

Veteran readers may recall I drew comparisons between CJ’s May 2021 colloquy with Planet Lockdown documentarian James Patrick and My Dinner with André in my second essay:

While I did not have the privilege of sitting down to dinner with CJ in person, I do feel like we channeled a bit of André Gregory and Wallace Shawn in the following epic exchange, which is really a conversation overlaying a meta-interview interwoven with my own meditations on his work.

An award-winning playwright, novelist, and political satirist, CJ has garnered the 2002 First of the Scotsman Fringe Firsts; Scotsman Fringe Firsts in 2002 and 2005; and 2004 Best Play of the Adelaide Fringe.

His plays have toured internationally, including at Riverside Studios (London), 59E59 Theaters (New York), Traverse Theatre (Edinburgh), Belvoir St. Theatre (Sydney), the Du Maurier World Stage Festival (Toronto), Needtheater (Los Angeles), 7 Stages (Atlanta), the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Adelaide Fringe, Brighton Festival, and the Noorderzon Festival (the Netherlands), among others.

Described as “a feral ferris-wheel of comedy, confusion, contradiction, obfuscation and bent-out-of-shape straight talking that leaps out of the room at you and harnesses you to its mischievous mindset” (Metro) and “puts the bourbon in Beckett” (The Guardian), CJ’s first play, Horse Country, is currently enjoying a revival at the Edinburgh Assembly Festival.

He followed that up with the 2005 Scotsman Fringe First–winning screwmachine/eyecandy, an “absolutely exhilarating” (The British Theatre Guide) “blistering revelation” (Time out New York), “sharp-toothed satire” (Village Voice), and “breathtaking event” (NYTheatre.com).

“A devastatingly brilliant tour de force” that “perfectly skewers all the little lies and double-thinks which comfort us” (STV), The Extremists is “a dark satire that playfully mocks the essential absurdity of the talking-head culture … taking on big issues like the loss of individualism and the looming apocalypse” (Atlanta Journal Constitution).

As if these plays weren’t proof enough of CJ’s divinatory powers, his 2017 dystopian science fiction novel, Zone 23, makes it look like he time-traveled to 2020 to take plot notes. The perpetually-medicated “Variant-Positive” could easily be NewNormalSpeak for Delta, Omicron, and BA.5 patients. In an evident nod to scientology, the Clear generation sounds like they’ve undergone experimental gene therapy to be “corrected.” Dissidents fall into the pharmaceutically resistant Antisocials, who inhabit quarantine zones. Even the idea of dividing the citizens into classes sounds like the medical apartheid being threatened at this very moment.

Indeed, CJ’s prognostications were so dead-on, he’s not sure how to complete the trilogy now that everything he intended to write about has come to pass. The second novel, for example, was supposed to take place during lockdown.

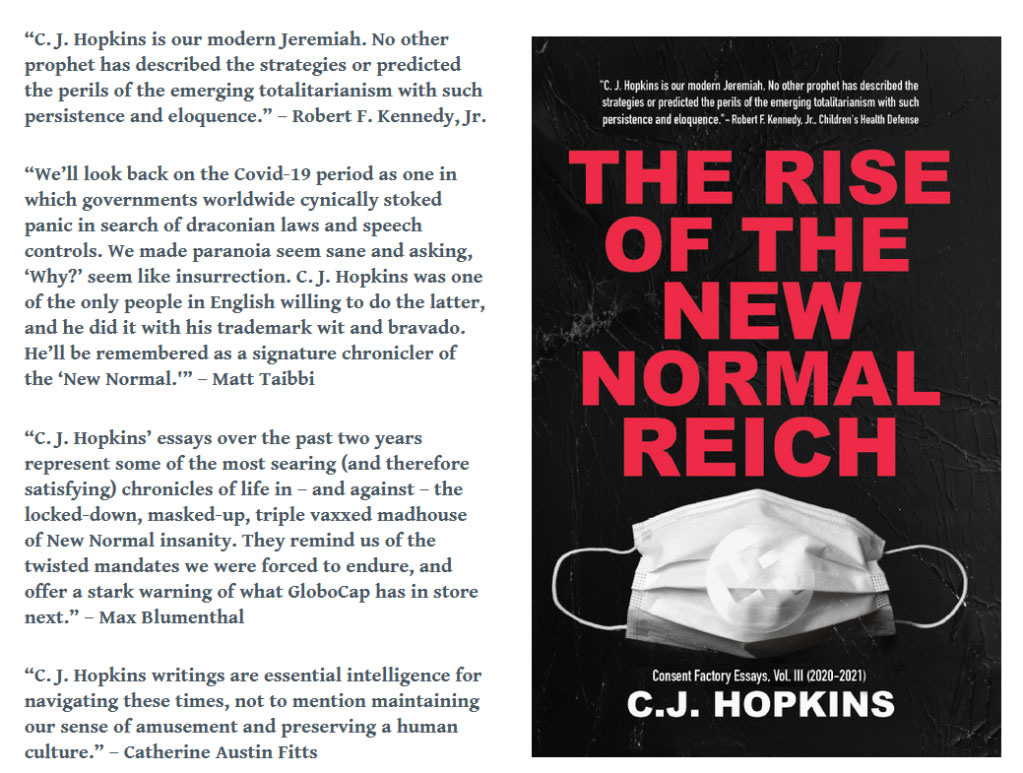

Consent Factory Publishing—a division of the ingeniously named Consent Factory, Inc.—publishes the books of CJ’s “that no ‘respectable’ publisher would ever consider publishing,” such as his latest, The Rise of the New Normal Reich: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. III (2020–2021), and his preceding collections Trumpocalypse: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. I (2016-2017) and The War on Populism: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. II (2018–2019). See his author website for the full list of CJ’s books.

The Consent Factory About page is a virtuoso performance, leading off with:

“Consent Factory, Inc. is a market-leading provider of post-ideological consulting services to private and public sector clients throughout the developed (and in some cases developing) world. Experts in the fields of behavioral and psychological conditioning, we offer an extensive range of individually-customized strategic-planning and project-implementation services in the following areas: education (all levels); parenting; advertising and marketing; media (traditional and alternative); governance; arts and culture; spirituality; science and medicine; and many others.”

Even the Contact page is rib-tickling. Those who subscribe to his Stack or support CJ in other ways enjoy the distinction of being listed as Publishers on the masthead as well as in his books—a badge I wear proudly given that CJ was the first person I subscribed to on Substack and one of the reasons I wound up here myself. Knowing a writer of his caliber and principle had chosen this platform gave me confidence in its quality and commitment to free speech.

To paraphrase our mutual favorite novelist, Kurt Vonnegut, “the accident willed,” so now here we are together chatting, and “if this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.”

Q&A #1

MAA: As you describe in your OffGuardian interview, you came of age during the 1960s and 1970s—a tumultuous period marked by consecutive assassinations, radical violence, extreme divisiveness, the Vietnam War, and Watergate. It’s no wonder you developed an anti-authoritarian streak and a healthy cynicism about the government. Yet there was also a budding optimism, a move toward harmony, reconciliation, and peace. When you reflect on the cultural zeitgeist and transformations of that era, how does it compare with what’s happening today?

CJH: These are generalizations, of course, but I think the early twenty-first century is a lot darker and more cynical, or desperate, than the 1960s, at least the early 1960s. The assassinations of the Kennedys and MLK, the carnage in Vietnam on TV night after night, the 1968 Democratic Convention, Kent State, the race riots, the murders of the Black Panthers, Malcolm X, COINTELPRO, and so on crushed the optimism I think you are referring to. There’s that famous Hunter S. Thompson quote from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas about how “with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”

I was born in 1961, so most of what I remember is the late 1960s and 1970s. The optimism, the hope, that arose out of the successes of the US civil rights movement was gone by then. People had got the message that the government and the ruling classes were not going to tolerate any kind of revolution, peaceful or otherwise. If you seriously challenged them, they would just kill you. People were angry, disillusioned, bitter. A lot of people withdrew, went “back to the land,” or to graduate school, or got a haircut and a job. I remember a lot of drugs, sex, violence, insanity. It was a pretty twisted, confusing time.

I think the most significant difference between that era and now is that the Cold War is over. We’re no longer living in a world dominated by competition between two fundamentally opposed ideologies ... which was the world I grew up in. Most of the serious revolutionary activity in the 1960s and 1970s was predicated, to some degree at least, on a socialist worldview, buttressed by, and dependent upon, the existence of the USSR. The disintegration of the USSR changed everything, more fundamentally than many people realize. Basically, we became a global-capitalist world in the early 1990s, a world dominated by one unopposed ideology ... a state of affairs that is unprecedented in human history.

If we want to understand the political and cultural forces and dynamics of our times, we have to begin there. Unfortunately, most of us are still viewing and analyzing events through the lens of the old pre-1989 world, a world that is no more.

Q&A #2

MAA: Your theory on the evolving post-ideological model of power is one of the more tantalizing topics you explore in The Rise of the New Normal Reich: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. III (2020–2021). In Globocap Über Alles, you write:

“What we are experiencing is a further evolution of the post-ideological model of power that came into being when global capitalism became a global-hegemonic system after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In such a global-hegemonic system, ideology is rendered obsolete. The system has no external enemies, and thus no ideological adversaries. The enemies of a global-hegemonic system by definition can only be internal. Every war becomes an insurgency, a rebellion breaking out within the system, as there is no longer any outside.

“As there is no longer any outside (and thus no external ideological adversary), the global-hegemonic system dispenses with ideology entirely. Its ideology becomes ‘normality.’ Any challenge to ‘normality’ is regarded as an ‘abnormality,’ a ‘deviation from the norm’ (as opposed to an adversarial ideology) and automatically delegitimized. The system does not need to argue with deviations and abnormalities (as it was forced to argue with opposing ideologies in order to legitimize itself). It simply needs to eliminate them. Opposing ideologies become pathologies ... existential threats to the health of the system.

“In other words, the global-hegemonic system (i.e., global capitalism) becomes a body, the only body, unopposed from without, but attacked from within by a variety of opponents, terrorists, extremists, populists, whoever. These internal opponents attack the global-hegemonic body much like a disease, like a cancer, an infection, or ... you know, a virus. And the global-hegemonic body reacts like any other body would.”

As you noted in your response above, many people still think in terms of ideologies, and they describe belief systems like wokeism and critical race theory in ideological terms. But really, those are just elements of GloboCap1’s monolithic “post-ideological ideology” enveloping the world, correct?

Do you think New Normality represents a hegemonic mashup of both fascism (GloboCap) and Marxism (socialism, wokeism, critical race theory), or is it irrelevant to speak in those ideological terms now?

How does it differ from Nazism? And Ingsoc?

CJH: Again, I think we’re in a new world, a new paradigm, where terms like “fascism” and “Marxism” are only useful up to a point and are often unhelpful. When I use the term “fascism,” I use it in the vernacular sense—i.e., not to refer to the twentieth-century totalitarian systems most people are familiar with but rather simply to mean “extreme authoritarianism” (which is typically the second definition in any dictionary). In my essays, I have tried to point out the similarities and differences between twentieth-century totalitarianism and the “New Normal,” which I understand as (a) a new, pathologized form of totalitarianism and (b) an entirely global-capitalist form of totalitarianism.

Twentieth-century totalitarian systems were reactionary attempts to thwart the evolution of global capitalism, attempts which failed. Of course, there are striking similarities because totalitarianism is totalitarianism, regardless of what form it takes, but the primary difference is that global capitalism is post-ideological. A globally hegemonic power system with no external adversaries does not need an ideology. Its ideology is “reality.” Ideologies are subject to challenge. “Reality” is not. Again, this is difficult for a lot of people to grasp because we have never before lived in a world completely dominated by one globally hegemonic ideological system, but that’s where we are now.

As for “wokeism,” I understand it as part and parcel of the implementation and consolidation of global capitalist ideology, or post-ideology. This gets complicated, but I’ll try to make it as simple as possible.

First, what capitalism does, ideologically speaking, is decode values. It is a values-decoding machine. It invades territories coded with despotic values (i.e., values established and enforced by the will of kings, despots, religious institutions, political parties … any type of ideological power system that dictates the values of a society), and it decodes those despotic values and substitutes its only value—exchange value—rendering everything and everyone a de facto commodity. A commodity has no inherent value. It is an interchangeable receptacle of value, which value is determined by the marketplace (rather than by the Church, the King, the Ayatollah, the President, tradition, custom, the community, et cetera). This was incredibly useful, this values-decoding machine, when we wanted to free ourselves from the tyranny of kings and the Church and establish something vaguely resembling democracy. But capitalism is just a machine. Left unattended—or worse, granted the power to rule societies—it continues to perform its function, decoding values … reducing everything and everyone to an essentially valueless commodity.

Second, as the global-capitalist values-decoding machine does its thing—rendering everything and everyone an essentially valueless, interchangeable commodity—it triggers a reactionary response from people and organizations who do not fancy having their values decoded or being transformed into an assortment of de facto commodities, receptacles for whatever “values” are selling well at the moment.

The way I see it, this is the fundamental conflict of our times, the global-capitalist decoding machine stripping societies, and ultimately, the entire territory of the planet—of despotic/social values and the reactionary resistance to that decoding operation. (Note that I am not using the term “reactionary” as a pejorative but simply as a description of a preexisting force reacting to the threat of an advancing force. Likewise, the term “despotic” simply means values established by the will of a ruler, or ruling system, or society, as opposed to values justified by something impersonal, like “science” or “empirical facts.”)

OK, think about “wokeism” in that context. Take the transgenderism debate, for example. Are the radical transgender activists trying to impose an ideology (i.e., a values system) on society, or do they represent a force which is decoding traditional values, stripping away the distinction between the two sexes, such that people become more and more like essentially valueless, interchangeable commodities? I would argue the latter. I haven’t delved into critical race theory enough to speak to it knowledgeably, but I assume that, if I did, I could probably identify the same values-decoding operation at work there.

Again, note that I’m not suggesting that values-decoding is “bad” in and of itself. It simply is what it is. I was born into the racially segregated American South, the traditional/racist values of which were decoded during the 1960s, and I’m not a fan of racism, so I think that was a good development. On the other hand, I like women and support women’s rights, so I oppose the decoding of the distinction between the sexes. At the same time, I support the rights of transgender persons—and other kinds of persons—to live their lives however they want but not to force their beliefs onto others.

Machines are just machines. They are neither good nor bad. Context matters. For example, I was “using pronouns” back in the 1980s—before they became part of an aggressive global-capitalist values-decoding operation and before a lot of today’s “radical trans activists” were born—but nowadays I find them oppressive.

Getting back to your main question, though, the point is, twentieth-century forms of totalitarianism sought to impose clearly articulated ideologies on society, whereas global capitalism does just the opposite. It strips society of traditional ideology/values … until anything can mean anything, and anyone can “be” anything, because the global-capitalist marketplace is the preeminent arbiter of social values.

Q&A #3

MAA: I’m currently listening to Speaking Out, a collection of lectures, speeches, and articles by Albert Camus, and it’s as if he wrote “The Artist as Witness of Freedom” (which isn’t long and I urge everyone to read) for this specific moment in history, this specific conversation.

Here are a few pertinent quotes:

“The unfortunate thing is that we are in the age of ideologies and of ideologies which are totalitarian—that is, which are sufficiently sure of themselves, of their imbecilic reason or of their shortlived truth, to see the world’s salvation in their own domination.”

“When one wants to unify the whole world in the name of an ideology, there is no other way but to make this world as fleshless, as blind, and as deaf as the ideology itself.”

“But with the intervention of ideologies of efficiency based on technology, the revolutionary by a subtle transformation has become a conqueror, and the two currents of thought have diverged. What the conqueror of the Right or Left seeks is not unity—which is above all the harmony of opposites—but totality, which is the stamping out of differences.”

That totality, that stamping out of differences seems to be what you are articulating when you describe a “globally hegemonic power system” that creates the all-immersive “‘reality.’”

I have read your essays on “reality” (e.g., here, here, and here), but I feel like I have a crisper grasp on what you mean by that thanks to your elucidation above.

Would you say this manufacturing of “reality” is equivalent to the “reality control” described in 1984?

“And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed—if all records told the same tale—then the lie passed into history and became truth. ‘Who controls the past,’ ran the Party slogan, ‘controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’ And yet the past, though of its nature alterable, never had been altered. Whatever was true now was true from everlasting to everlasting. It was quite simple. All that was needed was an unending series of victories over your own memory. ‘Reality control,’ they called it: in Newspeak, ‘doublethink.’”

“At all times the Party is in possession of absolute truth, and clearly the absolute can never have been different from what it is now. It will be seen that the control of the past depends above all on the training of memory. To make sure that all written records agree with the orthodoxy of the moment is merely a mechanical act. But it is also necessary to remember that events happened in the desired manner. And if it is necessary to rearrange one’s memories or to tamper with written records, then it is necessary to forget that one has done so. The trick of doing this can be learned like any other mental technique.”

CJH: I get in trouble when I talk about “reality.” I spent too much time in the theater, took too much LSD, and probably read too much Nietzschean post-structuralism in my youth. There is the common vernacular meaning of “real” (e.g., “Is that a real Matisse?” “It’s not real wood.”), and then there is “reality,” which is always manufactured, collectively, by society. I’m a playwright and an occasional theater director. That’s what we do in the theater. We manufacture “realities.” We revise “realities.” The theater is a “reality” lab. The performing arts are, generally.

I could go on and on about this, but let’s keep it simple and just say that there is reality (i.e., whatever you believe it is, personally) and there is “reality” (i.e., the concept a society uses to demarcate and enforce the boundaries of the “real”). That concept, “reality,” is not static. It is constantly revised according to the ever-changing needs of whatever system dominates the society in question. Thus, what is “real” in one society may be “unreal” in another society (e.g., the existence of God, or ancestral spirits, or certain diseases and psychiatric disorders). Or that is how it has been for most of history. Again, we are in an unprecedented situation in which one ideological system dominates the entire planet and has the power to dictate and enforce its “reality” globally.

So, there’s nothing inherently totalitarian about societies manufacturing “reality.” We’ve been doing it forever, since the dawn of civilization. And “reality” has evolved as civilization has evolved. What has changed is that, for the first time in history, one “reality” dominates the entire planet, not every single territory on earth, yet, but that is the trajectory. Global capitalism is conducting a “clear and hold” op, eliminating internal resistance and deviance from its “reality” and establishing ideological uniformity throughout the territory it occupies, which is the entire world. Being a globally hegemonic ideological system without any external adversaries, it doesn’t really have anything else to do.

The 1984 comparisons are apt. Orwell was painting a portrait of a totalitarian society, of course, and all totalitarian societies aspire to the establishment of complete control over every aspect of people’s lives, including their emotions, thoughts, and perceptions. That’s what makes totalitarianism totalitarianism. Global capitalism is just the first system that has had the power and means to achieve that globally. We aren’t there yet, but that’s where we’re headed.

Q&A #4

MAA: Even though we are living in a post–Cold War world, GloboCap appears to be attempting to resurrect those geopolitical dynamics with the war in Ukraine and vilification of Russia. They are tapping into the Cold War residue present in the cultural consciousness paired with the anti-Russia sentiment that has been seeded over the past several years as part of their efforts to torpedo Trump. They kept poking the Bear with NATO, militarization, and ethnic cleansing, and they had to know it would eventually react.

How does the Russia variable factor into your understanding of the post-ideological landscape? I realize this is no longer about democracy versus communism, so is it simply that Putin (and by extension, Russia) is one of those rogue characters threatening “reality” from within? Is he a convenient Goldstein being used to deepen social bonding through hatred, rage, and jingoism (GloboCap patriots vs. Putin/Russia)?

CJH: Yes, Russia is one of a handful of countries that have yet to be completely absorbed by GloboCap and thus continue to behave like sovereign nation states, at least occasionally. Global capitalism isn’t a bunch of bad guys sitting around in a room conspiring. It’s a complex economic/ideological system. Russia is both a component of the system and a pocket of resistance within the system. At the moment, it is flexing its muscles in an attempt to preserve what sovereignty it has left. Note how these pockets of resistance—Russia, Iran, Syria, Venezuela, etc.—are portrayed by the global capitalist propaganda machine not as geopolitical adversaries but as criminals, threats stemming from within the system.

Q&A #5

MAA: You’ve frequently discussed how the present incarnation of totalitarianism requires a “simulated democracy” and that it cannot operate overtly like twentieth-century totalitarianism.

In your April 2022 Geopolitics & Empire interview (@15:07), you stated:

“Global capitalism can’t go old-school totalitarian. It won’t work, right? So it has to go pathologized totalitarian. Instead of rolling out big flags with the swastikas and jackboots and parading through the streets, it can’t do that, so it has to hide inside of this pathologized narrative. ‘Oh no no, we’re not beating you to the ground because you don’t show allegiance to our ideology. We’re doing it for the public health!’”

And while chatting with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (@18:59), you said:

“I feel like the overarching message of the last two years … coming from power, has been, ‘Shut up, and get in line, because we’re the ones running things, and we can do this to you anytime we want.’ Bobby, it’s a more brazen totalitarianism than I’ve ever experienced from the West in my lifetime, and I can’t help but see it as a message.’”

In your Clifton Duncan Podcast2 interview (@38:03), you explained why you often reference the Third Reich, despite the blowback you get for it:

“The history of Nazism in Germany—it’s the history of the birth and the development of a totalitarian movement … that grew and spread and took power and committed the Holocaust, right? Which is horrible, I’m not minimizing it at all. That was a major part of that history, but the history does not reduce to the Holocaust. It’s the history of a political movement that took over society and imposed a totalitarian system on a society and started a bunch of wars. When I make the comparisons, what I’m doing is comparing one nascent totalitarianism to another totalitarian system.”

I have gotten similar flack for the same reasons, and I, too, explain that I am using it as an example of the progression from normality to totalitarianism, which I feel no book3 better captures than Milton Mayer’s They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933–45, so I was thrilled to hear you recommend that in this podcast and elsewhere. I think this quote by Mayer’s philologist friend articulates that transition painfully well:

“‘The dictatorship, and the whole process of its coming into being, was above all diverting. It provided an excuse not to think for people who did not want to think anyway.… Most of us did not want to think about fundamental things and never had. There was no need to. Nazism gave us some dreadful, fundamental things to think about—we were decent people—and kept us so busy with continuous changes and ‘crises’ and so fascinated, yes, fascinated, by the machinations of the ‘national enemies,’ without and within, that we had no time to think about these dreadful things that were growing, little by little, all around us. Unconsciously, I suppose, we were grateful. Who wants to think?

“‘To live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it—please try to believe me—unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness, acuity, than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, unless one understood what the whole thing was in principle, what all these ‘little measures’ that no ‘patriotic German’ could resent must some day lead to, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.’”

Do you think if GloboCap manages to corral everyone into a digital biosurveillance panopticon, we will shift from 1930s Germany to 1940s Germany? In other words, will they stop bothering with the illusion of freedom as Frank Zappa famously warned?4

“The illusion of freedom will continue as long as it’s profitable to continue the illusion. At the point where the illusion becomes too expensive to maintain, they will just take down the scenery, they will pull back the curtains, they will move the tables and chairs out of the way and you will see the brick wall at the back of the theater.”

CJH: The short answer is no. The simulation of democracy is an essential component of global capitalism. If I can be so cocky, or lazy, as to quote myself, this excerpt is from Pathologized Totalitarianism 101, an essay (and a chapter in the book) in which I tried to address this question at some length:

“Global-capitalist ideology will not function as an official ideology in an openly totalitarian society. It requires the simulation of ‘democracy,’ or at least a simulation of market-based ‘freedom.’ A society can be intensely authoritarian, but, to function in the global-capitalist system, it must allow its people the basic ‘freedom’ that capitalism offers to all consumers, the right/obligation to participate in the market, to own and exchange commodities, etc.

“This ‘freedom’ can be conditional or extremely restricted, but it must exist to some degree. Saudi Arabia and China are two examples of openly authoritarian GloboCap societies that are nevertheless not entirely totalitarian because they can’t be and remain a part of the system. Their advertised official ideologies (i.e., Islamic fundamentalism and communism) basically function as superficial overlays on the fundamental global-capitalist ideology which dictates the ‘reality’ in which everyone lives. These ‘overlay’ ideologies are not fake, but when they come into conflict with global-capitalist ideology, guess which ideology wins.

“The point is, New Normal totalitarianism—and any global-capitalist form of totalitarianism—cannot display itself as totalitarianism, or even authoritarianism. It cannot acknowledge its political nature. In order to exist, it must not exist. Above all, it must erase its violence (the violence that all politics ultimately comes down to) and appear to us as an essentially beneficent response to a legitimate ‘global health crisis’ (and a ‘climate change crisis,’ and a ‘racism crisis,’ and whatever other ‘global crises’ GloboCap thinks will terrorize the masses into a mindless, order-following hysteria).”

That doesn’t mean GloboCap won’t transform whatever remains of society into an enormous biosecurity dystopia where a perpetual “state of emergency” is in effect and we can have our lives digitally shut down any time we hesitate to comply with some baseless “public health” or “climate change” decree, or if the authorities decide we are “delegitimizing the democratic state” by protesting some blatantly ridiculous policy or criticizing or mocking the government or public-health authorities in some manner they feel is inappropriate or “threatening” (N.B. this is already the case in Germany). But it will be a smiley, happy biosecurity dystopia, where we’ll still be able to order affordable consumer products from Amazon, and physically go to the mall now and then, and enjoy a family holiday in a foreign country once or twice a decade, and sell each other individually hand-crafted artisanal doodads on Etsy, those of us who aren’t physically employed in the organic-fabric–paneled, ergonomic cubicle farm or infantilized, officeless “campus” of some subsidiary of a subsidiary of some transnational corporate behemoth or investment bank, or whatever.

And bugs. Yummy, yummy bugs!

Q&A #6

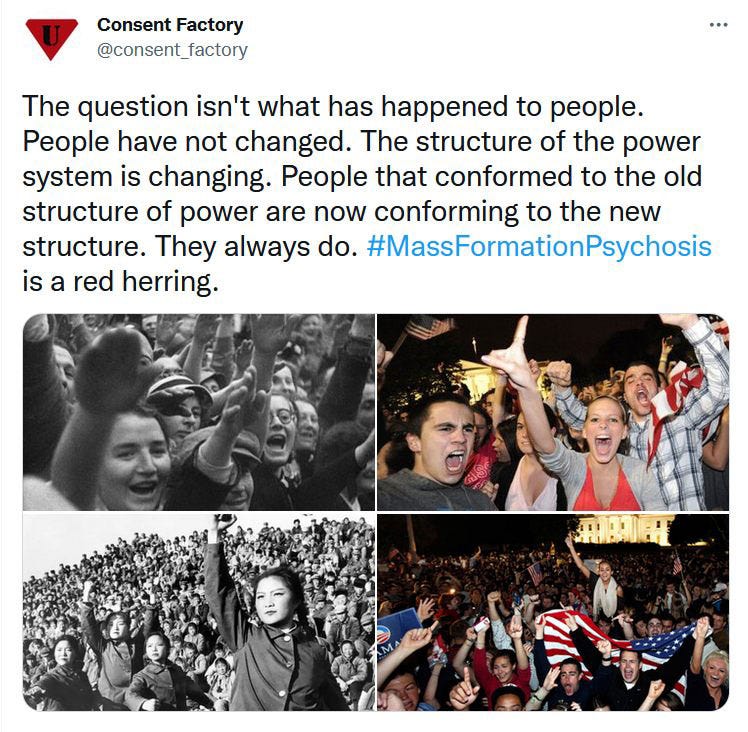

MAA: Haha, that sounds about right. Let’s talk about Mattias Desmet’s mass formation theory, which I know you have expressed differences with. This Facebook post, for example, kicked up quite a ruckus.

At the risk of oversimplifying, it feels like you’re on different sides of the chicken and egg debate. Whereas Mattias suggests mass formation precedes totalitarianism, you believe totalitarianism produces the mass formation, right?

Below are several of the clarifications you shared in that Facebook thread:

“The same people that conformed to the old structure of power (simulated democracy) are conforming to the new structure (pathologized totalitarianism). Their conformity looks different, not because the people have changed, but because the structure of power has changed.”

“It’s a red herring because it focuses your attention on the result rather than on the cause. You don’t defeat totalitarianism by ‘curing’ people of mass psychosis. You end the mass psychosis by dismantling the totalitarianism that caused it.”

“To those who are upset that I called Desmet’s theory a red herring ... my point is simple. It’s a red herring because the causality of the phenomenon is reversed. Mass psychosis doesn’t cause totalitarianism. Totalitarianism causes mass psychosis. Always. It is an essential part of the structure of totalitarianism. The people who conform to the dominant system of power will conform to ANY dominant system of power. Change the structure of the system of power, and their conformity to it will look different.”

I’ll be curious to get Mattias’s take on your perspective when I interview him. I do think you have a valid argument because you cannot have the all-encompassing propaganda campaign that creates the conditions for mass formation—isolation; sense of meaninglessness; and free-floating anxiety, frustration, and aggression—without first having a totalitarian system in place.

CJH: My essential criticism of Desmet’s mass formation theory is that it presupposes a psychological imbalance in society—the “isolation, sense of meaninglessness, free-floating anxiety, frustration, and aggression” that you cited—as a precondition of totalitarianism. Thus, it presents totalitarianism as the result or outgrowth of a society that is already somehow “sick.” Desmet is a psychologist, I believe, so it’s understandable that he sees things through that lens. However, I don’t believe it is useful, or accurate, to diagnose societies as “sick” or “healthy” or psychoanalyze them like individual patients. Nor do I believe that there has to be anything “wrong” or “dysfunctional” in a society for totalitarianism to take hold of it.

Totalitarianism can be imposed on any society if the government, or whatever structure rules it, controls the essential elements of power (i.e., the military, the police, the media, the culture industry, etc.). Once the transition to totalitarianism begins, you can count on roughly two thirds of the society either embracing it or acquiescing to it, not because they are in some vulnerable psychological state, but rather because they correctly perceive which way the wind is blowing and they don’t want to challenge the totalitarian regime and be punished for doing so. They are not hypnotized or under any other kind of spell. It’s pure survival instinct.

I realize my view upsets a lot of people because they want to believe that we are all fundamentally capable of resisting the rise of a clearly ultra-authoritarian or totalitarian ruling system, but we’re not, not all of us. Historically, only about one third of us are, and it typically isn’t even that many of us, or not at first. I don’t believe that is due to some flaw in human nature or some emotional or psychological condition. I cited the Milgram experiments in the introductory chapter of my book to try to make this point, because the results of his experiments line up with the historical records.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but most people are either perfectly content to conform to whatever type of society those in power impose on them as long as their basic needs are met, or they are not content, but they are cowards, so they stand by in silence. I don’t mean that as a judgment or an insult. Cowardice and the ability to abandon one’s principles (or not having any principles in the first place) are very positive traits to have if your goal is survival. When a society goes totalitarian or is otherwise occupied and radically transformed, it’s the rebels and dissidents who get lined up against the wall and shot, not the cowards and collaborators.

Q&A #7

MAA: That cuts to the crux of a topic I often explore in my essays (e.g., Letter to a Colluder; A Primer for the Propagandized: Fear Is the Mind-Killer; and Are You a Good German or a Badass German?)—namely, how are everyday, decent folks transmogrified into perpetrators of atrocities and instruments of tyranny?

In The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, Gustave Le Bon writes:

“[A]ll mental constitutions contain possibilities of character which may be manifested in consequence of a sudden change of environment. This explains how it was that among the most savage members of the French Convention were to be found inoffensive citizens who, under ordinary circumstances, would have been peaceable notaries or virtuous magistrates. The storm past, they resumed their normal character of quiet, law-abiding citizens. Napoleon found amongst them his most docile servants.”

Christopher Browning shares a similar observation from Zygmunt Bauman in Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland:

“For Bauman ‘cruelty is social in its origin much more than it is characterological.’ Bauman argues that most people ‘slip’ into the roles society provides them, and he is very critical of any implication that ‘faulty personalities’ are the cause of human cruelty.”

This sounds like what you’re capturing when you talk about people conforming to the societal structures imposed on them.

Also cited in Ordinary Men, Stanford Prison Experiment architect Philip Zimbardo came to an alarming conclusion that buttresses your point:

“‘Most dramatic and distressing to us was the observation of the ease with which sadistic behavior could be elicited in individuals who were not “sadistic types.”’ The prison situation alone, Zimbardo concluded, was ‘a sufficient condition to produce aberrant, anti-social behavior.’”

I agree with your earlier statement that there isn’t a roomful of cartoonish Cuban-cigar–chomping cabalists plotting out humanity’s destruction but rather that the manifestation of Gleichschaltung and Selbstgleichschaltung is an inevitable product of the totalitarian machine itself. That’s not to say that philanthropaths, tyrants, propagandists, colluders, and Covidians aren’t responsible for orchestrating, coordinating, implementing, and obeying what’s occurring, but they are acting according to the rules of their “reality,” and in the inverted morality of that world, they are actually performing acts of “good.”

Browning turns to Thomas Kühne in his own attempts to understand how this perverse recalibration of people’s moral compass occurs:

“Crucial to understanding the behavior of the ordinary Germans in uniform, [Thomas Kühne] argued, were the ‘myths’ of Kameradschaft and Volksgemeinschaft (comradeship and community). These powerful ‘myths’ must be understood as the Germans knew them, for they were the lenses through which Germans saw the world, constructed their reality, and derived the moral framework that in turn shaped their behavior.

“The myth of the Volksgemeinschaft derived from Germany’s euphoric sense and collective memory of unity transcending class, party, and confession.… Not only were Jews and other racial aliens excluded, but so were those whose behavior constituted an internal threat or potential treason against the German race. In short, conformity was an essential component of belonging.… The emotional power and need for belonging embodied in these two myths enabled the Nazis to preside over a ‘moral revolution,’ in which the western tradition of universalism, humanity, and individual responsibility based on a guilt culture was replaced by a shame culture that elevated loyalty to and standing within the group to be the new moral fulcrum of German society. Whether it be the Volksgemeinschaft as a whole, or the small unit within which a German fought, ‘the group claimed moral sovereignty.’

“The shame culture, making conformity a prime virtue, impelled ordinary Germans in uniform to commit terrible crimes rather than suffer the stigma of cowardice and weakness and the ‘social death’ of isolation and alienation vis-à-vis their comrades. This dynamic was intensified by several other factors. The first was that the ‘pleasures’ of comradeship and the ‘joy of togetherness’ derived from a heightened sense of belonging could be enhanced even further through transgression against the norms of members outside the group. ‘Nothing makes people stick together better than committing a crime together,’ Kühne noted. And second was the pernicious Nazi invention that Kühne dubbed the ‘morality of immorality.’ Both Hitler and various military commanders made the coercive zero-sum moral argument that pity and lenience toward the enemy and failure to overcome one’s personal scruples was a ‘sin’ against one’s comrades and future generations. The combination of all these factors created a ‘competition for mercilessness’ and a ‘culture of brutality’ within units. For Germans at large, the ‘outcome was the national brotherhood of mass murder—Hitler’s community.’”

Desmet also touches on this in The Psychology of Totalitarianism:

“This radical intolerance ensures that the masses are convinced of their superior ethical and moral intentions and of the reprehensibility of everything and everyone who resists them: Whoever does not participate is a traitor of the collective. Snitching is therefore commonplace; the population itself is the main branch of the secret police. Combined with the fourth factor, the opportunity mass formation offers to act out frustration and aggression without limit, this creates a well-known phenomenon: The masses are inclined to commit atrocities against those who resist them and typically execute them as if it were an ethical, sacred duty.”

I feel like understanding how this alchemic transformation occurs is key to discovering how to undo it, which is what you and I have committed our lives to doing.

Browning documented 12 men out of a battalion of 500 who excused themselves from shooting Polish Jews in the Józefów massacre when given the opportunity by their commanding officer. He quotes this striking observation from Zygmunt Bauman:

“The exception—the real ‘sleeper’—is the rare individual who has the capacity to resist authority and assert moral autonomy but who is seldom aware of this hidden strength until put to the test.”

Why do you think some people’s capacity for sociopathy is activated in times of crisis, whereas other individuals are immune to the forces compelling conformity?

Why is it those twelve men and people in our karass retain our core values of freedom, independent thought, aversion to tyranny, and a steady moral compass instead of succumbing to cultural and political pressures?

CJH: I don’t think there’s a blanket answer to that question, other than to say that for some of us, for a variety of reasons, the loss of our integrity and the betrayal of our principles is a prospect more horrible than whatever punishment the ruling classes can dish out. Speaking personally, I don’t regard myself as particularly virtuous or courageous. It’s just that giving up my autonomy, integrity, and abandoning my principles is out of the question. It is not an option. I don’t know who I would be if I did that. I certainly wouldn’t be able to respect myself. There’s a bit in the New Testament where Jesus asks, “What shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” I’m not a Christian, but there it is.

As for the question of how everyday, decent folks are transmogrified into perpetrators of atrocities and instruments of tyranny, as you put it, I think you answered that yourself with the Le Bon, Bauman, and Zimbardo quotes. Again, most people will conform to whatever type of societal structure is imposed on them by force as long as their basic needs are being met. Totalitarianism doesn’t transform people into monsters. It transforms the structure of the society such that they must behave as monsters in order to remain “normal,” i.e., in good standing with the totalitarian regime, and avoid being punished for nonconformity.

I think it’s difficult for those of us who place great value on personal autonomy to accept that there are people who don’t, but there are, and they are the majority, and they have been the majority throughout history. There is nothing “wrong” with these people. They just have different values, different priorities. Which is to say, we are not going to “cure” them or “awaken” them. As Bauman noted in that quote you cited, we are the exceptions, the freaks, not them.

You ask how we “undo” it. Well, if totalitarianism is an oncoming convoy of explosive-laden semi-trucks driven by formerly basically decent folks turned fascist fanatics, you don’t stop that convoy by trying to “awaken” those drivers … you stop it by shooting the tires of the trucks. The drivers will “awaken” on their own as they crawl out of the wreckage, or they won’t. That’s not really up to us.

Q&A #8

MAA: I emphatically agree with everything you said, CJ, and I feel “giving up my autonomy, integrity, and abandoning my principles” would be a fate worse than death, which I guess demonstrates how we lack the survival instinct you mentioned earlier—although I would argue we are cleaving to freedom, truth, love, and ultimately a yen to preserve humanity itself.

Shooting the semi-truck tires is a brilliant analogy. This is the part of the interview where I’m supposed to ask for practical solutions on how to dismantle totalitarianism so we can close on a note of hope. But you’ve already answered that question eloquently on numerous occasions. I’ll share some examples below for our readers as I write my way toward a different question, one as yet nebulous but which I trust will come into focus as I travel through your words.

During your December 2021 exchange with Gunnar Kaiser, you elaborated on one way in which you practice shooting the tires:

“The goal is not to show people the truth or disabuse them of some illusion that they have. The goal is to apply pressure from the other side. The goal is to apply the pressure by showing them the mirror because I believe most of these people are decent people with good hearts. I don’t believe that the vast majority of humanity are a bunch of sadistic monsters. They have been swept up into this movement. What I’m talking about is applying pressure from the other side, holding up the mirror and saying, ‘Look at the monster that you have become.’”

You also mention holding up a mirror in your Bakkie met Bergsma interview (@50:29):

“I’m holding up a mirror, and I’m saying, ‘Look at how you’re behaving. Look at how you’re acting. Because it looks just like other totalitarian systems.”

I often hold up the mirror myself (e.g., Letter to a Covidian, Letter to a Holocaust Denier, and Letter to an Agree-to-Disagree Relative), so I am happy to hear you think this is a worthwhile tactic. A reader once told me, after praising an article, that he could not share it with vax believers because people don’t respond well to insults. I saw his point, but I still feel strongly, like you, that we need to confront people with evidence of their fascistic behavior to keep chipping away at their delusions.

In addition to this approach, you also recommend creating “moments of friction” in your Dr. Mercola interview (@49:42) such as forcing staff to eject you from a coffeehouse for refusing to comply (which Naomi Wolf modeled beautifully in this tense encounter):

“The more moments they see of people standing up and saying, ‘This is insane, and it is wrong, and I’m not going to cooperate with it.’ Maybe I just have crazy faith, but I just feel like all these little moments of friction, they can build, and they can create the resistance that we need.”

And that friction needs to happen not only on an individual level but also on a grander scale, as you say in this James Delingpole interview (@56:06):

“We’re stuck inside of it, and really, the only choice we have is to create friction.… It goes back basic nonviolent civil disobedience principles.”

This is where populism comes in—and why it has been so necessary for GloboCap to wage war on populism, as you hilariously chronicle in Trumpocalypse: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. I (2016-2017) and The War on Populism: Consent Factory Essays, Vol. II (2018–2019).

I think the most exhilarating recent example of peaceful mass noncompliance is the Canadian truckers’ protest, which also sparked one of the most reprehensible propaganda mudslinging campaigns I’ve seen. The protesters shattered two years of COVID tyranny and achieved what Gustave Le Bon says is necessary to dethrone kings, as the epigraph of my Profiles in Courage: The Canadian Truckers reads:

“When the principle of authority is injured in the public mind it dissolves very rapidly.”

Defeatists think the Freedom Convoy movement failed because the protesters retreated before lives were lost to Tyrant Trudeau’s jackboot-stamping, but it injected hope, inspiration, and resilience into the worldwide movement for freedom and truth, sowing the seeds of resistance now blossoming in the form of protests ranging from the Dutch farmers to the Sri Lankan peasants. Trudeau was forced to show his tyrannical hand in a way that drew censure internationally (e.g., from literal Badass German MEP Christine Anderson), and he has soiled the illusion that Canada is a functional democracy.

In addition to acts of civil disobedience, we also need ways to express our solidarity and identify ourselves to one another as members of the unofficial White Rose Society. A while back, you launched a social media campaign encouraging people to deploy the upside-down red triangle with a ‘U’ for “unvaccinated,” which you use for your Consent Factory avatar. If you watched my Corona Investigative Committee presentation, you may have noticed the upside-down red triangle button on my hat. I have been wearing that since the mid-2000s, when my husband and I designed it along with a “Thought Criminal” t-shirt featuring the same triangle. Needless to say, your campaign resonated with me since I have been identifying as a political dissident for most of my life.

So donning that badge, whether on social media or on our person, is another way of generating friction as well as symbolizing our noncompliance to fellow dissenters.

In my second essay, COVID IS OVER! … If You Want It, I drew parallels between André Gregory’s and Wallace Shawn’s conversation in My Dinner with André and your electrifying dialogue with Planet Lockdown Director James Patrick, in which you noted (@55:48):

“So as much friction as all of us can create to force those moments where people have to make those choices, I think that’s the only way that we can prevent this [totalitarianism] from becoming our reality.”

James Patrick mentioned Étienne de La Boétie’s The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude, which I cited in that essay and continually return to as the secret to overturning tyranny:

“You can deliver yourselves if you try, not by taking action, but merely by willing to be free. Resolve to serve no more, and you are at once freed. I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces.”

In other words, “Do not comply.” This is so simple and yet so difficult for most people to grasp since we are programmed to obey from birth. But if the Covidians can break out of their Stockholm Syndrome, they will realize they hold the key to their own handcuffs, and they have the power to not only liberate themselves but all of humanity if we join together en masse in singing out, “NO!”

I found your Charles Eisenstein interview especially moving and loved the philosophical direction the conversation took. You revisit the theme of noncompliance with him (@54:42):

“This is a physical conflict, right? A new form of totalitarianism is being imposed upon us. It’s being imposed by force, and my role in the performance is to react to that imposition with anger.…

“I want to make this conflict visible. Everything isn’t fine. Everything isn’t normal. If I don’t conform to this ideology, police, armed police, will come and make me do it. And I want people to see that. I want it in their faces. I want people to have to decide, Do I conform to this thing, or is my role in this big theater performance to resist it, to push back against it?”

As an unintentional practitioner of the Stockdale Paradox, I deeply resonated with these lines (@40:16):

“Basically, my approach to life is affirmative, and I have some kind of weird faith in life, in people, in all forms of life. And I don’t think it [global totalitarianism] succeeds. It is something that has to implode.… I don’t think it’s a matter of stopping it. I don’t know if we can stop it, but … just like any other form that comes into being, the seeds of the death of that form are built into it, and as that form achieves its ultimate expression, the seeds of its death are also developing already inside of it and are at work, taking it apart, blowing it apart and ultimately destroying it and making way for whatever other forms are going to evolve. That’s the crazy faith that I have. I don’t think we can stop or push back on GloboCap … but I think many of us are feeding these seeds that eventually lead to what comes next.”

I love how you look at the world as a theater performance (@51:48):

“The way I look at the world is—I can’t help it, I’m a theater person—and in one sense, I look at it as a big theater performance, and I’ve been cast in this theater performance as me. And it wasn’t a mistake. The casting director knew what she was doing. I’m in the performance for a reason. I am who I am, what I am for a reason. It’s not an accident. Yes, my anger comes from all of the places that it comes [from] and it’s mixed up with all of the things … and every political book that I’ve ever read and every weird gaslighting experience I’ve ever had, and it’s all mixed up together in a bucket, and I’m me, and I’ve been cast in this role, and here comes the New Normal, and I trust my response.”

And this is poetry (@1:12:55):

“I have crazy faith in people. I actually like people. We are a big, beautiful, ugly, wonderful, horrible, peaceful, violent mess of an organism, and I love us, and I don’t think that we will tolerate the type of domination and control.… Yes, it may win for a while, but eventually, eventually, we will throw off that yoke.”

I feel like this quote by, once again, Camus, speaks to the core of who we both are at our essence:

“In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger—something better, pushing right back.”

I know you’ve been deeply influenced by Samuel Beckett, and your first play, Horse Country (which is enjoying a resurgence twenty years later and is currently playing at the Edinburgh Assembly Festival) was an attempt to figure out what there was left to say in the theater after Beckett.

Whereas I associate nothingness, emptiness, silence, and existential angst with Beckett, I feel an explosive exuberance for existence exuding from you and your work—an invincible summer to Beckett’s unwavering winter.

There’s a reason I’ve repeatedly used the term “barbaric yawp” for your work—there’s something thunderously Whitmanesque about you and your galvanizing humor.

So what did you discover you had to contribute after Beckett? How would you summarize the theatrical performance that has been your life and work?

CJH: I wouldn’t know how to begin to summarize “the theatrical performance that has been my life and work,” and hopefully I’ve got a few more years to add to the performance, but I’ll talk about Beckett, and writing, and the theater, and some other stuff a little bit.

I think every serious young writer has a literary idol that they have to do battle with and ultimately kill in order to find their own voice. For me, that was Beckett. As an aspiring, young, arrogant playwright in my twenties, I felt like I didn’t deserve to write anything if it wasn’t going to take the theater somewhere past the place Beckett had brought it to or at least open a door that could lead to such a place. I struggled with that for years and came up with Horse Country. Beckett ended things, or rather, pronounced them ended, like Nietzsche pronounced God, who was already dead, dead. The line in Ohio Impromptu, “nothing is left to tell,” haunted me. It was like a sentry standing at the gate of my work whose cryptic riddle I had to solve before I would be granted entrance.

Anyway, after pounding out a mountain of gibberish on an old IBM Selectric typewriter in an East Village tenement while the Butthole Surfers’ go-go dancers perched in the window across the airshaft eating fried chicken and throwing the bones down to the rats at the bottom of the airshaft for roughly a year, and then more on a computer the size of a Volkswagen that displayed text in orange on the screen of its humongous CRT monitor and took those eight-inch square floppy discs with the holes in the middle you could stick two or three fingers through, and having been thoroughly indoctrinated by my ex-wife, to whom I will be forever grateful, in the works of Artaud, Grotowski, the Open Theater, etc., I came up with Horse Country, which, the way I saw it at the time, and still see it, starts where Beckett ended.

Basically, if there is nothing left to tell, as Beckett put it, stop telling (i.e., saying things) and start doing things in the theater (i.e., the actual room where everyone is physically gathered) as opposed to the fictional room or world behind the fourth wall that you look in on as if you’re not there even though you can smell the performers right there in the room with you (and sometimes they throw avocados through it, that fourth wall, during a production of Curse of the Starving Class at the Public Theater, which kills the whole effect the fourth wall is trying to generate but never really does) is what I came up with, basically.

Experimental theater artists had been doing this for years, of course, dispensing with the fourth wall and creating communal events and/or rituals in the theater, but they were all doing it in an Artaudian anti- or contra-textual way, the text being the “enemy” of the event according to this school of thought, and even Brecht—also a big influence on me, obviously—was trying to prevent the spectators from succumbing to the power of the hypnosis-inducing fourth-wall thing with his Verfremdungseffekt. So there was Beckett, closing the book, putting an end to the literary type of crushingly boring museum theater that persists to this day, rendering the theater less and less relevant to anyone but the simulated aristocracy, and there were the neo-Artaudians, treating the text as if it were some sort of oppressive bourgeois leviathan that would snuff the life out of whatever spiritual–self-immolation ritual they were attempting to collectively create in some converted-garage sweatbox on the Lower East Side and then inflict on their friends from whatever little Ivy college they attended (and, later, on assorted European audiences) the moment they allowed it into their collective creation, and there was Brecht and his disciples, who were determined to deny the spectators the bourgeois enjoyment of the representational theater and … well, I went another way.

Horse Country is basically Abbott and Costello on acid. Except that the spectators are also on acid. Not at first, and not all of them, but a lot of them, ultimately. I’m not going to describe how it works in detail as that would take up an entire book probably, and I’d have to get into R.D. Laing and Deleuze and Guattari and how language operates for people undergoing psychotic episodes and spiritual experiences and so on, but it has to do with how we create “reality,” collectively, with language, and the power of ritual. If you are on a lot of LSD or having a psychotic episode, your perception is altered, physically altered. Our spiritual rituals used to do that also, before they were stripped of their power and reduced to empty simulations of themselves. It isn’t about watching a performance and rationally interpreting what it “means.” It is about having the wiring in your head physically altered by the drugs, the psychosis, or the performance so that you perceive reality differently. Theater still has the power to do that. Needless to say, the entertainment industry is negatively interested in the exercise of this power on the stage, so I have tried to sneak it into popular entertainment forms, writing plays that work like Trojan horses, which has worked surprisingly well so far.

Essentially, what I tried to do is marry Brecht and Artaud, and instead of banishing the text and trying to avoid turning on the Bourgeois Representation Machine, I turned the Bourgeois Representation Machine on, let it run, and screwed with it as it ran to demonstrate how it works, while it works, but doesn’t really work, because you can watch it working now, and yet still works, because the Bourgeois Representation Machine is really just a small-scale version of the much larger Machine that is creating (and destroying) “reality” on a moment-by-moment basis, which is the Machine I’m really interested in, because it is God.

OK, that sounds incredibly pompous and arrogant, which I try very hard not to sound too much like that these days. The thing is, it’s funny. All my plays are funny. And accessible. Horse Country is a vaudeville routine. Screwmachine/eyecandy is a TV game show. The Extremists is a PBS-type talk show. You don’t have to know anything about Brecht, Artaud, or psychosis, or God, or anything.

In any event, it doesn’t really matter what I think I’m doing or how or why I think I’m doing it. People are going to experience my plays and other works however they experience them. I’m just trying to entertain folks, basically, and make them question a lot of stuff we tend to take for granted, and … well, OK, screw with their heads a little bit to short-circuit the programming we’ve all been subjected to relentlessly since more or less the moment we were born in order to generate fleeting opportunities for us to recall that we are not “consumers” or any other type of talking meat puppets stumbling through meaningless lives on a big fucking rock floating in space for no reason and are really, each and every one us, attributes of some Spinozan God-thing that we don’t understand, so maybe we should cease and desist from attempting to dominate and control everything and win some competition that isn’t even taking place and treat each other accordingly.

Q&A #9

MAA: Tears are welling up in my eyes, CJ, and I feel like I’ve just read the ending of a new beloved book and want to wrap around to the beginning as I’m not yet ready to leave this experience. Thank you for bringing all of your being, your wit, and your heart to this collaborative endeavor. I believe we have co-created something we can both be proud of, and calling this process an honor and a joy doesn’t feel strong enough.

You may not think of yourself as “particularly virtuous or courageous,” but you meet Kurt Vonnegut’s definition of a saint according to his last speech:

“You meet saints everywhere. They can be anywhere. They are people behaving decently in an indecent society.”

They can line us up against the wall and shoot us, but our words will stand as a testament to the truth of what occurred—as opposed to their “reality”—during this time of darkness, and the friction they create will help write The Downfall of the New Normal Reich.

Returning, once again, to Camus, I will close with a quote from his speech to Salvador de Madariaga:

“So how should we not be tempted to tell you in unison this evening what the dying Turgenev wrote to Tolstoy: ‘I have been fortunate to be your contemporary.’”

—“The Option of Freedom,” Speaking Out

CJH: It’s been a pleasure, Margaret ... thanks again for suggesting we do this and making it happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment