“!”

|

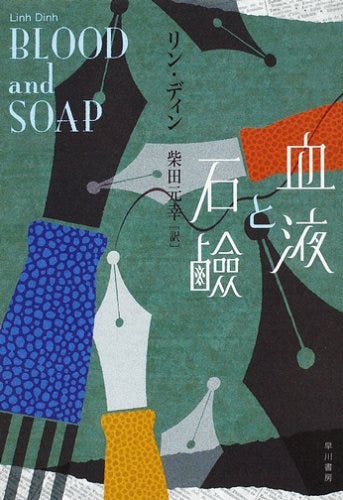

Note: So exhausted, I need a little breather from article writing, so below is a short story from my collection, Blood and Soap (2004). Though the book has been translated into Italian and Japanese, and selected by the Village Voice as one of the best for that year, it never sold well. On Amazon, it has just six reviews! With me now canceled, my stories and poems have even fewer readers. To put the most positive spin on this, I’m an eyes closed, nose pinched acquired taste, like poutine sprinkled with grasshopper flakes. If I remember correctly, I wrote this in 2000 in Saigon, though much of Blood and Soap was written in Certaldo, Italy in 2002-03.

*********************************

In The Workers newspaper of October 10, 2000, there was a curious item about a fake doctor. A certain Ngo Thi Nghe had been practicing medicine for over ten years on a false degree, which she procured, it is speculated, by killing its original owner. She had all the accoutrements of medicine, a white suit, a thermometer, a bedpan, a syringe, many bottles of pills, but no formal knowledge of medicine. In fact, she had never gotten out of the eighth grade. The mortality rate of her patients, however, was no higher than usual, and she was even defended by some of her clients, after all the facts had come out, for saving their lives. “A most compassionate doctor,” said one elderly gentleman.

There are so many scams nowadays that this case drew no special attention. Every day there are news reports of fake lawyers, fake architects, fake professors, and fake politicians doing business without the proper license or training. A most curious case in recent memory, however, is that of Ho Muoi, who was accused of being a fake English teacher. From perusing innumerable newspaper accounts, I was able to piece together the following:

Ho Muoi was born in 1952 in Ky Dong village. His family made firecrackers until they were banned because of the war. Thereafter the father became an alcoholic and left the family. Although Ho Muoi was only six at the time, he knew enough to swear that he would never mention or even think of his father’s name again. His mother supported the children, all five of them, by carrying water and night soil for hire, a backbreaking labor that made her shorter by several inches. She also made meat dumplings that she sold on special occasions.

Ky Dong Village is known for a festival, held every January 5th, in honor of a legendary general of a mythical king who fought against a real enemy two or three thousand years ago. The festival features a duck-catching demonstration, a wrestling tournament for the boys, a meat dumplings making contest for the girls, and, until it was banned because of the war, a procession of firecrackers.

Those who’ve witnessed this procession of firecrackers describe a scene where boys and girls and gay men jiggle papier-mâché animals and genitals strung from bamboo sticks amid the smoke and din of a million firecrackers.

But the excitement from the festival only came once a year. For the rest of the time, the villagers were preoccupied with the tedium and anxieties of daily life. Most of the young men were drafted into the army, sent away and never came back, but the war never came directly to Ky Dong Village.

When Ho Muoi was ten, his mother enrolled him in school for the first time. He was slow and it took him a year to learn the alphabet. He could never figure out how to add or subtract. His worst subject, however, was geography. It was inconceivable to him that there are hundreds of countries in the world, each with a different spoken language. Every single word of his own language felt so inevitable that he thought it would be a crime against nature to call a cow or a bird anything different.

Ho Muoi could not even conceive of two countries sharing this same earth. “Countries” in the plural sounds like either a tautology or an oxymoron. “Country,” “earth” and “universe” were all synonymous in his mind.

Ho Muoi’s teacher was a very sophisticated young man from Hanoi. He was the only one within a fifty-mile radius who had ever read a newspaper or who owned even a single book. He even fancied himself a poet in his spare time. He did not mind teaching a bunch of village idiots, however, because it spared him from the bombs and landmines that were the fate of his contemporaries. In the evening he could be found in his dark room reading a Russian novel. The teacher was short and scrawny and had a habit of shutting his eyes tight and sticking his lips out when concentrating. Still, it was odd that he managed to attract no women in a village almost entirely emptied of its young men.

Whenever this teacher was exasperated with his charge he would shout “!” but no one knew what the word meant or what language it was in so it was dismissed as a sort of a sneeze or a clearing of the throat.

At twelve, something happened to Ho Muoi that would change his whole outlook on life. He was walking home from school when he saw a crowd gathering around three men who were at least two heads taller than the average person. The men had a pink, almost red complexion and their hair varied from a bright orange to a whitish yellow. They were not unfriendly and allowed people to tug at the abundant hair growing on their arms. “Wonderful creatures,” Ho Muoi thought as he stared at them, transfixed. One of the men noticed Ho Muoi and started to say something. The words were rapid, like curses, but the man was smiling as he was saying them. All eyes turned to look at Ho Muoi. Some people started to laugh and he wanted to laugh along with them but he could not. Suddenly his face flushed and he felt an intense hatred against these foreign men. If he had a gun he would have shot them already. Without premeditation he blurted out “!” then ran away.

When Ho Muoi got home his heart was still beating wildly. The excitement of blurting out a magical word, a word he did not know the meaning of, was overwhelming. He also remembered the look of shock on the man’s face after the word had left his mouth. He repeated “!” several times and felt its power each time.

Ho Muoi would think about this incident for years afterward. He recalled how he was initially enraged by a series of foreign words, and that he had retaliated with a foreign word of his own. In his mind, foreign words became equated with a terrible power. The fact that his own language would be foreign to a foreigner never occurred to him.

The incident also turned Ho Muoi into a celebrity. The villagers would recall with relish how one of their own, a twelve-year-old boy, had “stood up to a foreigner” by hurling a curse at him in his own language. Many marveled at the boy’s intelligence for knowing how to use a foreign word, heard maybe once or twice in passing, on just the right occasion and with authority. They even suggested to the schoolteacher that he teach “the boy genius” all the foreign words from his Russian novels.

The schoolteacher never got around to doing this. He was drafted soon after, sent south, and was never heard from again. As for Ho Muoi, he became convinced that, given the opportunity, he could quickly learn any foreign language. This opportunity came after Ho Muoi himself was drafted into the Army.

His battalion served in the Central Highlands, along the Truong Son Mountain, guarding supply lines. They rarely made contact with the enemy but whenever they did, Ho Muoi acquitted himself miserably. He often froze and had to be literally kicked into action. What was perceived by his comrades as cowardice, however, was not so much a fear of physical pain as the dread that he would not be allowed to fulfill his destiny.

The war was an outrage, Ho Muoi thought, not because it was wiping out thousands of people a day, the young, the old, and the unborn, but that it could exterminate a man of destiny like himself. And yet he understood that wars also provide many lessons to those who survived them. A war is a working man’s university. Knowing that, he almost felt grateful.

Ho Muoi also had the superstition (or the inspiration) that if the war eliminates a single book from this earth, then that would be a greater loss than all the lives wasted. The death of a man affects three or four other individuals, at most. Its significance is symbolic and sentimental, but the lost of a single book is tangible, a disaster which should be mourned forever by all of mankind. The worth of a society is measured by how many books it has produced. This, from a man who had never actually read a book. Ho Muoi had seen so few books, he could not tell one from another; they were all equal in his mind. He never suspected that war is the chief generator of books. A war is a thinking man’s university.

In 1970 or 1971, after a brief skirmish, they caught an American soldier whom they kept for about thirty days. The prisoner was made to march along with Ho Muoi’s battalion until he fell ill and died (he was not badly injured). This man was given the same ration as the others but the food did not agree with him. Once, they even gave him an extra helping of orangutan meat, thinking it would restore his health.

As the prisoner sank into delirium, the color drained from his face but his eyes lit up. He would blather for hours on end. No one paid him any attention but Ho Muoi. In his tiny notebook he would record as much of the man’s rambling as possible. These phonetic notations became the source for Ho Muoi’s English lessons after the war. I’ve seen pages from the notebook. Its lines often ran diagonally from one corner to another. A typical run-on sentence: “hoo he hoo ah utta ma nut m pap m home.”

The notebook also includes numerous sketches of the American. Each portrait was meant as a visual clue to the words swarming around it. Ho Muoi’s skills as an artist were so poor, however, that the face depicted always appeared the same, that of a young man, any man, really, who has lost all touch with the world.

Ho Muoi was hoping his unit would catch at least one more American so he could continue his English lesson, but this tutor never materialized, unfortunately.

Though all the English he had was contained within a single notebook, Ho Muoi was not discouraged. The American must have spoken just about every word there was in his native language, he reasoned, through all those nights of raving. And the invisible words can be inferred from the visible ones.

Words are like numbers, he further reasoned, a closed system with a small set of self-generated rules. And words arranged on a page resemble a dull, monotonous painting. If one could look at the weirdest picture and decipher, sooner or later, its organizing principle, why can’t one do the same with words?

Everything seems chaotic at first, but nothing is chaotic. One can read anything: ants crawling on the ground; pimples on a face; trees in a forest. Fools will argue with you about this, but any surface can be deciphered. The entire world, as seen from an airplane, is just a warped surface.

A man may fancy he’s making an abstract painting, but there is no such thing as an abstract painting, only abstracted ones. Every horizontal surface is a landscape because it features a horizon (thus implying a journey, escape from the self, and the unreachable). Every vertical surface is either a door or a portrait (thus implying a house, another being, yourself as another being, and the unreachable). And all colors have shared and private associations. Red may inspire horror in one culture, elation in another, but it is still red, is still blood. Green always evokes trees and a pretty green dress.

Ho Muoi also believed that anything made by man can be duplicated: a chair, a gun, a language, provided one has the raw materials, as he did, with his one notebook of phonetic notations. If one can break apart a clock and reassemble it, one can scramble up phonetic notations and rearrange them in newer combinations, thus ending up with not just a language, but a literature.

At the time of his arrest, Ho Muoi was teaching hundreds of students beginning, intermediary and advanced English three nights a week. For twenty-five years, he had taught his students millions of vocabulary words. He had patiently explained to them the intricacies of English grammar, complete with built-in inconsistencies. He had even given them English poems and short stories (written by himself and the more advanced students) to read. When interrogated at the police station, however, our English teacher proved ignorant of the most basic knowledge of the language. He did not know the verb “to be” or “to do.” He did not know there is a past tense in English. He had never heard of Shakespeare and was not even aware that Australians and Englishmen also speak English.

In Ho Muoi’s made-up English, there are not five but twenty-four vowels. The new nuances in pronunciation force each student to fine-tune his ear to the level of the finest musician. There is a vast vocabulary for pain and bamboo but no equivalent for cheese. Any adjective can be used as a verb. I will hot you, for example, or, Don’t red me. There are so many personal pronouns, each one denoting an exact relationship between speaker and subject, that even the most brilliant student cannot master them all.

By sheer coincidence, some of Ho Muoi’s made-up English words correspond exactly with actual English. In his system, a cat is also called a cat; a tractor, a tractor; and a rose, inevitably, perhaps, a rose.

Some of his more curious inventions include blanket, to denote a husband. Basin, to denote a wife. Pin prick: a son. A leaky faucet: a daughter.

Ho Muoi’s delusion was so absolute, however, that after he was sentenced to twenty-five years for “defrauding the people,” he asked to be allowed to take to prison a “Dictionary of the English Language” and a “Dictionary of English Slang,” two volumes he himself had compiled, so that “I can continue my life studies.”

It is rumored that many of his former students have banded together to continue their English lessons. Harassed by the police, they must hold their nightly meetings in underground bunkers, lit by oil lamps. Their strange syllables, carried by the erratic winds, crosshatch the surrounding countryside.

But why are they doing this? You ask. Don’t they know they are studying a false language?

As the universal language—for now—English represents to these students the rest of the world. English is the world. These students also know that Vietnam, as it exists, is not of this world. To cling even to a false English is to insist on another reality.

A bogus English is better than no English, is better, in fact, than actual English, since it corresponds to no English or American reality.

Hoo he hoo ah utta ma nut m pap m home.

Source: Postcards from the End

No comments:

Post a Comment