FASCISM, NEWNORMALISM AND THE LEFT

by Paul Cudenec

Sometimes secondhand books can come into our possession in ways that make it quite clear they need us to read them.

Such was the case with Le fascisme italien by Pierre Milza and Serge Berstein, (1) which reached me by means of a random sequence of events including a friend moving flat, an unexpected traffic jam and a small public park on the outskirts of Paris.

It did not disappoint and, as I am about to explain in more detail, helped me to see a number of crucial issues more clearly.

Firstly, it confirmed that, despite constant claims to the contrary, fascism was not at all anti-capitalist, but extremely pro-capitalist.

Secondly, it presented interesting parallels with the Coronavirus-linked totalitarian mindset so dominant in 2020, which I am calling ‘newnormalism’.

Thirdly, it sparked some wider reflection on my part about the participation of most of the left in this 21st century authoritarianism and how that relates to my own anti-fascist position.

FASCISM AND CAPITALISM

It is well known, I think, that Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator, began his political career on the left and, when he started building a movement immediately after the First World War, the initial programme that attracted support was left-wing, with anarchist influences.

However, as Milza and Berstein make abundantly clear, this prototype fascism was quickly and drastically ditched as Mussolini realised the only way he was going to gain the power he craved was with the support of capitalists and big landowners.

Much much later, at the end of the Second World War, in a desperate last-ditch attempt to rally the Italian people behind them in the face of defeat, the hardcore fascist Saló republic rediscovered their socialist side, but it was all hopelessly too late.

Having lived through the fascist ventennio (20 years), the population were not going to fall for any more redwashing attempts or superficial anti-bourgeois posturing. They had seen clearly that fascism in power defended the interests of Capital, rather than the people.

The authors trace this story back to 1910, when the Italian Nationalist Association was founded with “the support of certain business circles, in particular that of heavy industry”, (2) who had a very obvious direct vested interest in promoting the nationalist call for Italian participation in the approaching war in Europe.

It was Mussolini’s sudden support for Italy going to war (on the Allied side) that led to him being thrown out of the socialist party, the PSI, splitting from others on the left. This left him ideally placed to benefit from capitalist funding, though it is not clear whether his conversion to the war cause was actually motivated by this consideration.

It is known that Mussolini received money from the French government and from pro-war businessmen like Filippo Naldi.

The first fascist general assembly in 1919 took place in a hall in Milan lent by a group of wealthy capitalists.

Funds started to roll in from business, banks and big landowners

Fascism benefited greatly from the ruling classes’ fear of a Bolshevik-style revolution in Italy, with post-war waves of strikes and a rural movement which reclaimed land from rich property owners.

Explain the authors: “The fear born in the world of the country landowners as a result of the land occupation movement greatly outlived the phenomenon itself and helped pushed them into the arms of fascism, through fear of a challenge to property rights”. (3)

Business organisations such as Confagricoltura and Confindustria were set up to defend capitalism. Fascism was happy to win favour by providing them with foot soldiers, squadristi, who physically attacked trade unionists and leftists in a wave of “preventative counter-revolution”. (4)

This, say Milza and Berstein, represented fascism’s big break and funds started to roll in from business, banks and big landowners.

Moreover, the fascists started receiving the support of local authorities, the army and the police in their fight against leftist ‘subversion’. They were the system’s emergency weapon against the threat of revolution.

“Prefects, magistrates and officers of the Carabinieri, let the fascists carry on and assured them of impunity. The moment that the State started to crumble, the bourgeoisie, so frightened by the popular uprising of 1919-20, lent their support to fascism’s reactionary violence”. (5)

In November 1920, for instance, violent fascist squads descended on Bologna, where the radical left had gained control of the local council. There were nine deaths and more than 100 injuries.

Elsewhere, in the next couple of years, they smashed up trade union and co-operative HQs and attacked working-class districts, wielding clubs and revolvers to force strikers back to work.

By now the fascists had stopped pretending to be left-wing and were openly singing the praises of capitalism and economic liberalism. (6)

Fascist economic policies were all in the interests of the ruling class.

“Mussolini himself set before the future party a manifesto which no longer owed anything to the leftist tendencies of 1919. In the economic realm it was absolute liberalism, with the State indulging in no intervention or nationalisation, or any fiscal measures deemed ‘populist’. On the political and social side, a strong State was to be created, capable of imposing the ban on strikes in the public sector”. (7)

This was authoritarian capitalism, meant to please “the big money interests from whom Mussolini was now seeking political and financial backing”. (8)

As the future dictator said himself: “We are liberal economically, but we will never be so politically”. (9) This was a question of sacrificing political liberalism in the interests of economic liberalism, aka capitalism. (10) (For more on the little-appreciated similarities between fascism and liberalism, see this article on the orgrad website)

Once the fascists were in power, the clamp-down on opposition was ruthless. Strikes were banned and workers found themselves defenceless against their bosses.

Fascist economic policies were all in the interests of the ruling class. When finance minister Alberto De Stefani reformed the tax system in 1923 this “was above all to the profit of the rich”. (11)

He offered tax breaks for foreign investors, did away with the “red tape” of bodies controlling food prices and rents, ended state funding for co-operatives and halted land reforms which threatened the interests of rich landowners.

After 1925, in the face of economic crisis, the pure economic liberalism of the Manchester School went out of the window, in favour of state intervention.

But this was intervention in the interests of business and Capital, not in the interests of the Italian people whom fascism mendaciously claimed to represent!

‘Development’ was at the forefront of fascist plans, as is the case with all industrial capitalists. More land was cultivated and an infrastructure of roads, new towns and industrial estates was built.

“A vast programme of public works was undertaken, carried out by private firms, who were offered lucrative contracts by the State. Electrification of the rail system began, with the construction of tunnels on the Rome-Naples and Bologna-Florence lines. A massive roadbuilding programme was entrusted to ANAS (Azienda Nazionale Autonoma delle Strade), created in 1928, which oversaw the showcase construction of big toll motorways, the first in Europe”. (12)

This was nothing other than a bailing-out of the capitalist economy by the pro-business fascist state, for which the cost would ultimately have to be borne by the public.

Ring any bells in 2020?

Banks were also treated to fascist largesse, notably BCI, saved by the Italian state with a massive influx of money.

Note the authors: “There was neither socialisation nor nationalisation. The State became capitalist; it guaranteed the property of most of the shareholders and their future dividends. The only socialisation was that of the losses, assumed by the public purse”. (13)

In 1931, Mussolini even set up a body, L’Istituto mobiliare italiano, with the role of helping businesses in financial trouble, declaring that this was “a means of energetically driving the Italian economy towards its corporative phase, which is to say a system which fundamentally respects private property and initiative, but ties them tightly to the State, which alone can protect, control and nourish them”. (14)

But the emphasis was very much on the big businesses and financiers allied with the fascist regime. Economic crisis saw numerous small and medium-sized firms go to the wall or gobbled up by big companies, as the fascist state aided this concentration of wealth into ever-fewer hands. (15)

“As for the working classes,” add Milza and Berstein, “they paid the price for this alliance, with unemployment, reduced wages and higher cost of living”. (16)

Fascist corporatism, with its officially-approved phoney trade unions, was supposed to bring together workers and bosses in the interests of the nation, but did nothing of the sort: “It allowed big industry and financial groups to use the State’s arbitration and power of coercion to reinforce their positions and impose their law on their employees”. (17)

“Far from being destroyed by fascism as the first proto-fascist manifesto suggested, Italian capitalism found in it a defender which managed to save it from revolution or collapse and went on to reinforce its structures and its means of action”. (18)

It was not for nothing that the bankers of J.P. Morgan boosted the fascist regime with a $100m loan between 1925 and 1927 (19) or that Winston Churchill praised, during a 1927 visit, Mussolini’s success in defending Italy from what he termed international subversion. He meant the radical left. (20)

FASCISM AND NEWNORMALISM

Already, in the above account of Milza and Berstein’s work, there are some striking parallels with society a hundred years after the fascists seized power in Italy, in particular regarding the way in which a pro-capitalist regime will use the power of the State not to control big business, but to rescue it from collapse, defend its wealth and impose its interests on the people.

But the similarities become still more alarming when we consider the ideological framing of the fascist mission.

Everything was to be “new” under fascism. A new creed for a new Italian people in a new Italy. The old days were gone for good and nothing would ever be the same again. Mussolini’s dictatorship was the New Normal.

The regime tried to change the date to symbolise this complete rupture, insisting that party members stopped thinking in terms of the 1920s or 1930s and instead spoke of Year 8 or 10 of the fascist New Order. (21)

It also tried to abolish handshakes – not because they might spread disease but because they represented the decadent old world that had been left behind. Socially-distanced fascist salutes were preferred. (22)

It hoped that a fascist future would be carried forward by a new brainwashed generation, building a cult of youth and a structure of youth organisations which aimed to foster “obedience and fanatical attachment to the regime”. (23)

Fascism differed from other pro-capitalist and authoritarian regimes in that it aimed to reshape, to reinvent, everything about society.

Milza and Berstein stress “its totalitarian character, in other words the way in which it tried to direct and control every aspect of every individual’s activity and thinking”. (24)

These early 20th century fascists, like the newnormalists today, were obsessed with “remodelling the social body and transforming it radically”. (25)

Mussolini dreamed of “the fascisisation of the spirit, complete transformation of society and the creation of a new man… with a radically new conception of the world”. (26)

It is when we look at what this new fascist existence would actually involve that we can begin to understand the agenda behind this early experiment in behavioural change.

Explain the authors: “It was about reducing all Italians to the same model, that of the fascist man. This ‘new’ man was not to be defined by ideas, actions, faith or social utility but by a ‘style’, the fascist custom, taken straight from futurist raptures. Speed, dynamism, efficiency and decisiveness were its main components”. (27)

Futurism, one of the great inspirations for Italian fascism, was the ideology of industrialism, of the man-machine, of the surrender of all that was human and natural to the giant cogs and turbines of technological progress.

One of the great successes of the fascist period in Italy was the acceleration of the working rhythm

20th century industrial capitalism needed a new kind of human being – a regimented, automated human being – to fit in with its brave new world and the unimaginable profits and power that could roll off its factory conveyor belts.

Inconveniently, actual human beings – reactionaries, oldthinkers, enemies of progress – did not seem to want to remould themselves to suit the requirements of capitalist machinery, so compulsion was required.

“Only a strong power could impose on the masses the sacrifices necessary for the accumulation of capital”, (28) note Milza and Berstein and, indeed, one of the great successes of the fascist period in Italy was “the acceleration of the working rhythm”. (29)

Mussolini wanted to “modernise” Italians in the way that Margaret Thatcher modernised British people in the 1980s or in which Emmanuel Macron has been trying to modernise the French with his own brand of neoliberal authoritarianism.

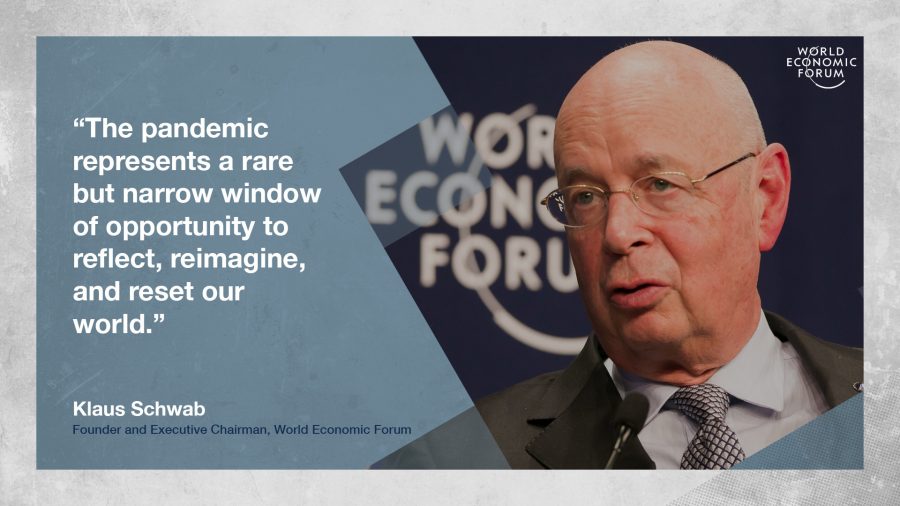

And today there is a global attempt to modernise us all in order to suit the requirements of 21st century capitalism and its nightmarish Fourth Industrial Repression.

We are to be reduced to fearful, isolated, obedient and dependent cattle owned and exploited by a ruthless and truthless financial elite.

Once again, we have not been shuffling fast enough towards the abyss on our own, so “strong power” has been activated, on the back of the Coronavirus hysteria, to shove us deeper into the jaws of the life-consuming industrial beast.

The propagandistic language, hysterical mass brainwashing and police-state coercion used by the newnormalists for their “Great Reset” are straight out of Mussolini’s hundred-year-old handbook.

NEWNORMALISM AND THE LEFT

There is at least one significant difference between the fascist period and today’s newnormalism and that concerns the left.

As we have seen, Mussolini came to power on the back of attacking the left, earning him the gratitude of a ruling class scared by the prospect of revolution. Once in power, he did all he could to destroy it, with most left-wing radicals fleeing Italy or ending up in jail.

Indeed, my reading Milza and Berstein’s book led to a conversation with a woman whose grandfather, a left-wing activist in Italy, had been forced to escape the fascist regime and settle in France.

How can it be that the left – theoretically anti-capitalist and anti-fascist – finds itself marching in step with totalitarian capitalist newnormalism?

Today, however, there is a resounding silence from most of the left in the face of the newnormalist totalitarian coup.

Many of them, even some self-described anarchists, are enthusiastic supporters of the fascistic “lockdown” and compulsory mask-wearing. They regard support for the system and its framing of reality as socially responsible and therefore “left-wing”. Anyone who challenges the system is irresponsible and therefore “right-wing”.

How on earth has this happened? How can it be that the left – theoretically anti-capitalist and anti-fascist – finds itself marching in step with totalitarian capitalist newnormalism?

Putting aside the possible factors of sheer gullibility and deceitful bad faith, I can see two reasons for this total ethical and ideological collapse.

The first is the way that much left-wing thinking has drifted away from direct opposition to capitalism. The beginning of this was, I think, the failure to understand that industrialism is nothing other than capitalism and that technological progress is not the same thing as social or human progress.

The left has therefore evolved within the framework of industrial capitalism, essentially accepting its basic premises. As a result, the left often has nothing more to propose than a reform of capitalism, or its relabelling.

Increasingly it has been sidetracked into defending the right of various minorities to be fully accepted within capitalist society.

Nothing wrong with that in itself, but it does not tackle the central injustice of the full-spectrum rule of a tiny elite class and the ways in which this central injustice is hidden from view and excluded from the realm of political discussion. Indeed, it helps to hide it still further from view.

Neither does it challenge the domination of industrialism and often reinforces its myth of “progress”.

The second reason concerns human nature. It has become widely accepted on the left that there is no innate human nature, that our minds are born as blank slates and, like machines, we are “programmed” by family and society to become who we are.

In fact, this misunderstanding arises from the broader failure to understand that human beings are part of nature, which is a planet-sized collective organism (see Nature, Essence and Anarchy).

Denying the existence of human nature effectively involves denying us all our primary freedom – to be who we are.

It automatically justifies outside imposition on each individual, and indeed community, in order to ensure that we are all “programmed” the right way.

This attitude can begin with a relatively harmless over-emphasis on formal top-down education (rather than allowing people to discover and think for themselves), but ends up with an insistence on controlling and policing every aspect of everyone’s lives.

Both these factors in fact stem from the contamination of left-wing thinking by liberal ideas. Liberalism is, of course, the philosophy of capitalism. Economic liberalism was, as we have seen, a central pillar of historical fascism.

So it should come as no surprise that a strong liberal influence on left-wing thinking should result in it siding with the capitalist fascism of newnormalism.

Left-liberals have taken on board the ruling class’s elitist belief that the mass of people are incapable of thinking or acting properly without strict supervision and training.

Total freedom, for them as for our rulers, is thus a frightening concept, one which has to be permanently penned in with qualifications and restrictions.

In this they are adopting the opposite ideological position to that of classical anarchism (real anarchism) and organic radicalism.

The mainstay of this current of thinking, to which I associate myself, is that human (and animal) nature is innately co-operative and that it is only the domination and exploitation imposed on us for many centuries that has forced people into an unhealthy condition of narrow individual selfishness combined with pathological dependence on authority.

For real anarchists, the smashing of the chains of tyranny would release humankind to live in the way it was always meant to live, to fulfil its true potential.

The idea is that human society would arise organically from human nature, and our belonging to the Earth, that we would create a society that suits who we are.

The opposite point of view says that there is no innate tendency towards mutual aid and social co-operation, indeed no innate tendency towards anything at all.

It says that human nature is entirely malleable and should therefore be forced to adapt to whatever way of living is deemed necessary by those in charge of society.

For Victorian industrialists in England and 20th century fascists in Italy, this meant forcing complex and multi-dimensional human beings into the square hole of industrial servitude.

For today’s big business transhumanists and newnormalists, this means forcing living human beings to adapt to the demands of their sinister and dehumanised “smart” totalitarian world.

From my point of view, a very clear divide has opened up here. On one side of this are those of us who are motivated by a love of life, of people and of nature and who seek to bring about a future in which all of this can thrive.

On the other side are those who are motivated by the vision of a certain future system, the end result perhaps of hundreds of years of industrial so-called progress, and who see life, people and nature as subservient to that.

If human nature doesn’t fit with their system and their way of thinking, that human nature has to be changed by whatever means necessary.

To me, this mindset is extremely noxious. It is a kind of sterile hygienism, an attitude which regards everything “bio” as a hazard, anything natural as dangerous and imperfect, in contrast to the artificial symmetry and cleanliness of its machine-based futuristic dream.

I have previously labelled this ideology “vitaphobic“, meaning that it amounts to nothing less than a hatred of life itself.

It comes as no surprise to realise that historical fascism was part of this vitaphobic trend. It is harder to accept that the same is also true of much of the contemporary left, including groups and people I was, until recently, happy to work with.

I am every bit as much opposed to vitaphobic newnormalist leftists as I am to fascists

These kind of leftists invariably and inevitably feel the need to dismiss anyone who does not entirely share their dogma as being “right-wing” or “fascist”.

But, in fact, here my opposition to their vitaphobic ideology comes from the very same place as my opposition to fascist vitaphobia.

This does not mean that they are themselves “fascists”, which was a specific historical phenomenon, but that, in 2020, they have aligned themselves with a life-hating ideological trend of which historical fascism was also part.

This is why I am every bit as much opposed to vitaphobic newnormalist leftists as I am to fascists and consider their ideology equally dangerous to the future of humankind and our Mother Earth.

1. Pierre Milza and Serge Berstein, Le fascisme italien 1919-1945 (Paris: Editions de Seuil, 1980). All subsequent notes refer to this work.

2. p. 30.

3. p. 68.

4. p. 71.

5. p. 110.

6. p. 104.

7. pp. 110-11.

8. p. 111.

9. Benito Mussolini, cit. p. 113.

10. p. 119.

11. p. 223.

12. p. 232.

13. p. 245.

14. Mussolini, cit. p. 246.

15. p. 247.

16. p. 248.

17. p. 283.

18. p. 276.

19. p 228.

20. p. 316.

21. p. 194.

22. p.213.

23. p. 203.

24. p. 198.

25. p. 275.

26. p. 198.

27. p. 212.

28. p 414.

29. p. 283.

No comments:

Post a Comment